This week has a dual focus.

Firstly, procrastination is examined. Why do we procrastinate when we want to do hard tasks? It’s not just learning; procrastination affects many different everyday tasks we know we need to do but may initially be daunting. We go into the neurological rationale behind procrastination, and learn techniques on how to avoid it.

Secondly, we learn about memory formation and access. Included are techniques for building chunks using memory tricks, and how memories work in the brain.

Procrastination

It’s easier than most people think to avoid procrastination.

The reason most people in this day and age procrastinate is because of our constant distracted states in the 21st century. We all carry around a device with infinite possibilities for distraction, and that’s just the start. We procrastinate because, when faced with an undesirable task, our brain wants to divert away that negativity. It comes up with ideas of alternative things to do, allows you to be distracted, etc. When the distractive activity happens, the brain releases dopamine, as most distracting activities do (and are sometimes optimised for). This creates a vicious cycle through which we become “chronic procrastinators”, as the neural pathway is reinforced. In this way, procrastination is very similar to addiction.

A useful analogy is to think of the crazy people that used to microdose themselves with poisons to “build up resistance”. Sure enough, they could stomach a large dose of arsenic/cyanide/what-have-you, but it was wrecking havoc on their insides and lead to an early death in the long term. Procrastination won’t kill you, but the more procrastinating you do, the more your brain sees it as a viable alternative to doing the work you actually need to do. Like building up tolerance to a drug, it can become harder and harder to actually whip your focus back on willpower alone.

A note on willpower; it’s pretty much useless when you try and use it too much. It should be viewed as a precious resource, limited and only to be used in important situations sparingly. It’s very fragile, made even moreso because we often link our self-esteem to our capacity for willpower. It has its place in destroying the procrastination habit, when used sparingly. More on that later.

The Procrastination Habit

Procrastination is ultimately a habit. We all know how hard to kick they can be. Habit formation works similarly to chunking; creation of new chunks requires conscious processing of input data to your brain. Through practice, you go from processing that data in your conscious mind to your subconscious mind. Eventually, you don’t even consider finer details of whatever chunk you’ve created unless you need to; you have a subconscious understanding of the chunk’s subject matter as a whole. Examples include riding a bike, backing out of a driveway, or executing a maneuver in the martial arts (see Josh Waitzkin’s Art of Learning for an excellent book all about this). Habit formation works in the same way; initially conscious, leading to subconscious execution without even thinking about it.

It can be helpful to think of your subconscious mind as your inner “zombie” army. They don’t really process input data deliberately; they rely on ingrained knowledge through practiced chunking, or habits you’ve formed over time.

Structure of a Habit

There are four stages to a habit.

- Cue: An event that triggers the habit.

- Routine: The response made by your inner zombie in response to the cue.

- Reward: Dopamine-releasing response when the routine is completed.

- Belief: Our mental rationale to keep a habit going; believing it’s beneficial, or that you’re physically unable to kick said habit.

Crucially, habits are perpetuated through the final Belief stage of the habit. We often rationalise our habits. An example of rationale for procrastinating is “I’ll eventually burn out if I don’t let my hair down for a minute”. How do we avoid this pattern of thinking?

Process vs Product

First of all, don’t kick yourself for feeling negative about learning activities at their outset. Our hunter-gatherer brains work against us here; it’s a perfectly natural human response to tough, brain-intensive tasks. It’s not actually this negativity that triggers the bad habit formation though; it’s your response to it that matters more.

This is where the distinction between Process and Product comes in to things. The brain triggers negative, procrastination-breeding feelings when confronted by thoughts of a deliverable; the product. Instead, focusing on the learning process will help trigger a much more beneficial mental state for productive work.

- Process: “I will work for 25 minutes on that important analysis”.

- Product: “I need to finish this important analysis for XYZ”.

What quote puts you in a more anxious mental state? Focusing on the process is a much more sustainable way to approach challenging activities; not just learning. This is why the Pomodoro method is so useful; by blending in 25 minute work periods with 5 minute breaks, and focusing on the process of that work rather than the product of it, you remain optimally focused and avoid procrastination. This is how we build better work habits.

The brain also prefers process over product. By overloading our working memory with thoughts of a large deliverable we can get anxious and procrastinate by doing simpler work (or no work at all). When focusing on process, we can filter away distractions more easily because our subconscious brain knows it’s time for work; rather than giving in to the distraction under the rationale that we’ll get “right back to it” after the distraction is complete.

Mobilising your inner zombie army: Beating Bad Habits

The cue is the first stage of the habit. It’s what leads you to generate the bad habit in the first place, and what triggers the response. For procrastination, the trigger might be something like a colleague discussion you can overhear in the kitchen that you want to join, or glancing over a particularly enticing bookmark to your favourite infotainment platform.

Common cue types are:

- Location

- Time

- Sensory Stimuli (Emotional/Physical)

- Reactions

Now we know what the first stage of a habit is, we can attack our procrastination at the source; the cue. You can’t avoid the cues. We don’t live in sensory deprivation chambers. But we can control our response to the cue. We can do this by enacting a plan when we notice the cue. When noticing a whatsapp message pop up from your group chat, follow a plan you’ve determined to put your phone in your bag for a while instead of opening it up and responding immediately. By enacting and sticking to plans, you’re replacing the routine part of the habit with something better; starting the process of building good habits in place of bad ones. It also avoids the willpower issue; you aren’t using willpower to pull your attention away from your zombies screaming at you to perform the Routine response to the cue, you’re just doing a different Routine response instead.

When things go right, you should reward yourself. This also helps in the setting of more positive habits. At the end of particularly productive pomodoro intervals (if you decide to use them), grab a snack to get that surefire dopamine & serotonin kick. Build up that zombie army in favour of your new positive work habits. Be the pavlovian dog! After a while, you may enter a flow-state, where we feel in a positive mood due to breakthroughs you make as you progress through your learning material (the understanding gained from new chunk formation is very motivating). This creates a positive feedback loop, which we always want to maximise our exposure to!

Finally, you need to believe in your new habits. A good tip is to engage with communities of like-minded individuals who are all motivated to do what you’re doing, whether that’s learning, or using a technology, whatever. This belief replaces your old beliefs in your procrastination habit being unchangeable and inevitable, even if you’re “faking it” at first. It’s still neurologically powerful.

The process for developing good habits is ultimately the same as the process for reversing bad habits. You just need to overwrite your trigger response to a cue shared with a bad habit with a good one. This is how we overcome procrastination. By enacting your plan, rewarding yourself and building confidence in your better habits, your bad habits are minimised.

Juggling Life & Learning

Task lists are really common. But did you know that by setting them at the very end of a day (before you go to bed), your subconscious mind, your zombie army, processes a lot of the cognitive load you would otherwise have swirling around your conscious mind in your working memory? Your zombies will help process that information, in ways that you aren’t even aware of, to help you perform better.

Initially, it’s really hard to estimate how long it takes to do something. I always wondered how people were able to accurately estimate how long it would take to learn a certain amount of material, or perform a task at the beginning of my career. As you learn more about a certain problem area, and more generally as you get older, you get better at estimating how long it takes to complete things. This is vital for good planning, as it enables you to appropriately plan time and stop you getting overwhelmed.

Setting a quitting time is just as important as scheduling in learning time. The reason for this is that you don’t just harm your ability to work at your best by overlearning (see the distinction between cramming and learning over time in my notes for Week 1. By handing the day’s material over to your diffuse mode, you solidify your learning experiences, which is a vital step in creating any real understanding about a subject, rather than disparate learned facts and methods.

One last tip for this section; how does one swallow a frog? Swallowing the Frog is the concept of doing the most difficult task on the day’s docket first to minimise cognitive load, dread and procrastination. Don’t fool yourself into thinking that doing busy-work is productive when you have the most pressing/most difficult/most undesirable task still staring you in the face. Swallow the frog, get it out of the way, be happy.

Memory

I’ll be straight with you. The human brain sucks for remembering facts, figures, words, code. I mentioned how the brain didn’t really evolve to cope with distraction very well, because not too long ago an ignored distraction could get us killed. When was the last time a hungry lion stopped its prey and asked what year England won the World Cup?

However, our brains are incredible at managing sensory, visual and spatial information. We store that type of information into memory extremely efficiently. I often catch myself humming a song I remember from a long time ago, but I realise I don’t remember its name. We can often recognise where we are based on the look of the landscape around you.

The more senses you are able to hook into things you need to remember, the stronger the memories of that information will be. This, combined with repetition, is what facilitates the movement of information from working to long-term memory. This is also the reason why handwriting, rather than just visually and audibly processing information, helps solidify learning. All these lecture notes are adapted from short handwritten notes I make watching the course videos.

What is Long Term Memory?

Long term memory of newly learned material is directed by the hippocampus. Individuals without a hippocampus in their brain (removed through surgery for epilepsy for instance) suffer from chronic amnesia. A sense for what this is like can be gained by watching the film Memento, by Christopher Nolan. They may have memories, but they struggle to develop new ones.

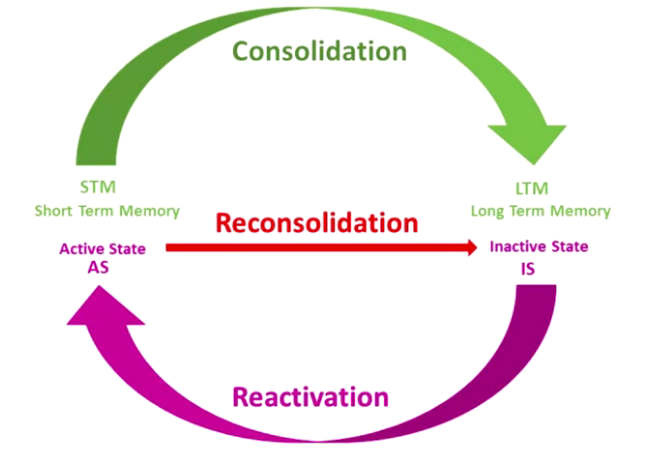

Memories are not static objects. They aren’t just committed to memory and left there permanently unchanged. Committal of memories is called consolidation. Every subsequent access of a memory alters it, through a process called reconsolidation. The below image is a schematic map of what this process looks like. Reconsolidation happens all the time, even through sleep.

Neurologically, this may be linked to the presence of astrocytes in the brain. Astrocytes are a type of glial cell, which is a cell type that supports neurons in the brain. They provide nutrients, maintain ion balance, amongst other functions. The key finding from postmortem investigation of Einstein’s brain, performed to see what enabled him to think so creatively in such a technical field, found that he had a significantly elevated astrocyte count compared to the typical human; aside from that it was a completely normal brain. Further research shows that transplanted human astrocytes implanted into mice significantly increased their ability to solve puzzles. Make of that what you will. The image below shows Astrocytes in green and Neurons in blue.

Creating Memories

This section goes into understanding some techniques for creating memories more solidly.

Firstly, note that memories are formed much more strongly when organised into meaningful groups. It’s easier to remember three separate events that happened on the same date when you group these events in your mind under that date, for instance.

One memory trick to help facilitate chunk formation and committal of information into long term memory is the Mnemonic. The following mnemonic is for the Electromagnetic Spectrum:

R oman ~ M en ~ In vented ~ V ery ~ U nusual ~ X Ray ~ G uns

Radio Wave, Micro Wave, Infrared, Visible Light, Ultraviolet, X-Ray, Gamma Wave respectively. Imagining a bunch of centurions running around blasting each other with X-Ray guns is an absurd concept but linking the mnemonic to learn the names (and wavelength order) of the spectrum is useful when first developing the chunk, and can be discarded when the information is fully chunked in my mind.

Another technique is the Memory Palace. This memory trick works by visualising a familiar place, and assigning objects like furniture and wallpaper to pieces of disparate information that you want to group together “artificially”. It is possible to memorise the full order of a deck of cards with just a small bit of practice using this technique.

Many people turn their noses up at these techniques. A common cause of complaint is that by creating artificial groupings to commit information to long term memory, you are not “properly” learning the material, whatever that means. However, research shows that those who use these techniques:

- Outperform those who don’t when tested on the subject matter.

- Form chunks more readily and easily.

- Create big picture templates to generalise chunks from more easily.

- Use the learned material more creatively.

This is why mnemonics are so ubiquitous in language learning. By injecting wild neural connections through absurd, silly, wacky when forming chunks right from the beginning, you’re laying the groundwork for your diffuse mode to more readily make links to other chunks. Creative neural links are formed. This is extremely important, as creativity helps you harness information in natural, spontaneous ways, so your understanding is much deeper than it otherwise would have been.

Summing Up

The key takeaways from this week’s learning are as follows:

Procrastination

- Procrastination is entirely manageable through the formation of better work habits.

- The first way to do this is to recognise your procrastination cues, which is often focusing too hard on the end-goal when embarking on a task. Focusing on the process is much healthier for the mind.

- Rewarding yourself during the creation of better habits helps overwrite bad habits. Replacing the response to a cue is the key. Belief in your new, better habits is the final step to ensure they remain intact.

- Willpower isn’t necessary if you make sure that you have a backup plan for potential distraction cues. If it must be used, make sure it’s used sparingly as it’s a fragile, finite resource.

- Habit formation is very similar to chunk formation; it’s all about committing information into long-term memory in ways that you can process subconsciously (using your zombie army).

- Ensure your plans and todos are sacrosanct, especially in the early stages of overwriting procrastination habits with better work habits. Eat your frogs by doing the work you dread the most first.

Memory

- Memories aren’t static. They’re neurological objects that are subject to change, even when we aren’t necessarily aware that we’re processing those memories. This has positive and negative effects.

- Human memory is not optimised for learning knowledge-based material. It is optimised for sensory and spatial knowledge. Employing certain techniques (memory tricks like mnemonics and memory palaces) to exploit these helps commit information to long term memory more easily.

- Memory tricks aren’t to be sniffed at; as they often incorporate additional information into the learning of new material, you will understand the material on a deeper level and utilise it more creatively once that understanding is formed, despite the idea seeming counterintuitive at first.

Twitter

Google+

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Pinterest

Email