This is a second in a five part series on the Learning How To Learn course on Coursera. For context on this series of posts, please see the first post here.

This week is all about the technique of “chunking”; a technique used to improve upon one’s ability to commit new complex information to memory in a sustainable way, and improve transfer learning potential for the future.

What is Chunking?

- Chunking helps the learning process more efficient; bundling related material and concepts into “chunks” enables you to synthesize the material more effectively.

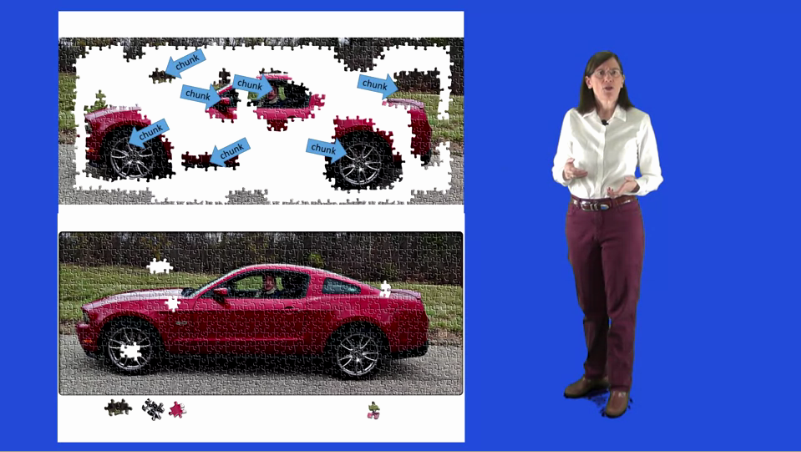

- Think of it like assembling a jigsaw; the bigger picture helps learning stick as you develop an understanding of the details and minichunks that make up the “chunk”.

- Focused Mode deliberately links chunks together through deliberate learning efforts. The Diffuse Mode links together chunks at random to see what sticks.

- By blending bottom-up (small details / facts / techniques / methods) and top-down (big picture stuff) learning of a subject area, the resultant chunk can then be built upon for future learning of other subject areas using transfer learning, like a Neural Net!

How to Chunk

Chunks begin as small minichunks. Starting small and building around the chunk while incorporating knowledge of the overall context (the big picture) is what makes them effective.

The general process for creating new mental learning chunks is as follows. /NB: Different types of learning require slightly different, but still conceptually similar methods of chunking/.

- Make sure you’re fully focused on the subject matter you’re trying to learn. Remember the 4 slots in your Working Memory (your RAM)? Having the TV on, being in a distractive environment, amongst other things, takes up those slots. By not committing your full attention to the learning process, the brain won’t be able to work at its full capacity to learn the material. It’s like introducing a RAM bottleneck into your system because you’re too busy running a resource hungry (and dopamine inducing) program in the background.

- Understand the basic idea. Really understand it. One common learning fallacy is the inability to synthesize information you “understand”. Learning is asymmetrical and ultimately useless if you require prompting from the material to synthesize it. More on this later.

- Understanding the overall context. This is the point at which the Top-Down Learning meets the Bottom-Up Learning, and a chunk becomes fully formed. A useful way for gaining context is by skim-reading, going through the section headers, or going through a picture walk of the material you’re attempting to learn (top-down) before getting into the weeds of the detail (bottom-up)

The above picture helps given an idea of how learning the structure of chunks can help you understand the big picture; from the chunks you’ve learned you can piece together the big picture by linking together “person”, “wheel”, “window”, etc. This is similar to how CNNs (Convolutional Neural Networks) work.

Illusions of Competence

Rereading material you’ve already read doesn’t work. It’s just a way for us to make ourselves feel like we’re learning, it’s an easy shortcut that gives us the dopamine kick we crave from “understanding” the material as we read it. But this doesn’t give a long-term and useful committal of the material to Long Term Memory. It means we’ll be familiar with the subject matter upon prompting, but we can’t use it spontaneously to link concepts or transfer/build upon that knowledge elsewhere. It is not yet chunked. Instead, minitesting (recalling information without looking at the material) should be practiced after starting on new minichunks. This is a great idea because this retrieval process helps build up those neural links that will make sure that minichunk of information, and the chunk built from it, remain in memory and useful to the learner.

Similarly, concept maps only really work if you are working at a suitably high level. It’s impossible to build concept maps from the minichunk level, they need to be built upon and generated into fully formed chunks first before they can be mapped across. Rereading as part of a spaced repetition system can work, but it requires a framework and synthesis/retrieval step anyway, so it’s not really rereading.

A final note on illusions of competence; you may not realise it, but your environment may be aiding in your understanding/recall of learned chunks. You need to be environment independent when learning new information, otherwise you’ll only be competent in the place you did the original learning! Removing those environmental queues by synthesizing the information in different environments is an important part of the chunk forming process.

Tips on forming chunks

Learning new chunks requires the use of as many slots in working memory as possible. This is why it’s important for first remove distractions. Once the information is a fully formed chunk, all that material that your mind was previously scrambling across your whole brain to develop neural links around does not require nearly as much neuron activity. The chunk can be attached to one of the existing slots while learning new things to facilitate transfer learning. The course uses the analogy of an octopus, deliberately connecting the slots and their neurons on a meta level. Once the learning is chunked, those neuronal connections are established already, and the octopus doesn’t need to manually connect them all together again to retrieve the concept they describe.

Making mistakes is an important part of the learning process, which is why mini-tests and retrieval is so important. It’s OK if you can’t, but correcting those mistakes reinforces the budding neural links making up the chunk, so it’s important to do that practice! Combining synthesis with feedback will result in better formed chunks.

From experience, the first steps towards becoming an expert in any academic topic is to create conceptual chunks about the main theorems/results/techniques of the discipline. These mental leaps between the chunks helps unite what may at first seem like very scattered bits of information by providing meaning and context.

Lastly, metaphors and analogies work really nicely in the creation of chunks. Much like mnemonics in language learning; the mnemonic is really useful to help facilitate the recall of vocabulary, and the successful recall of the word strengthens the neural link and the chunk is strengthened in memory. It eventually falls out of relevance as the chunk (in this case, a word) is sufficiently well-formed. They act as catalysts/jumping off points for the chunk formation.

Seeing the big picture

Motivation is caused by neurons that release dopamine. Drugs cause addiction by tricking these neurons into firing when under their influence.

The amygdala is the part of the brain in which emotions are regulated. Emotions are necessary for cognition.

Creativity when linking chunks together (combining them in new and unexpected ways) requires a library of chunks. One might be surprised to find out how applicable chunks are to seemingly unrelated subject matter when the brain connects them in diffuse mode. This is why Bell Labs had their wheel & spoke structure to simultaneously optimise individuals for deep work and teams for serendipitous discovery through creative linking of knowledge; this happens on a micro level in the brain between chunks if one has a suitably large chunk library.

Chunking may initially seem difficult. This is because the brain hasn’t gotten used to the “chunking” process. As the brain gets better at doing it, the chunks become larger and more abstract, enabling better “big picture” thinking. This requires the creation of lots of chunks, so it’s important to get started with chunking as soon as possible!

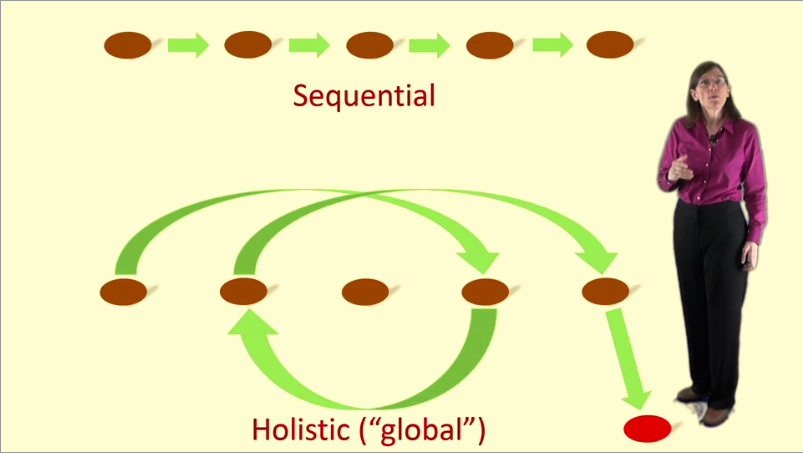

There are two ways to come to solutions; and they lend themselves better to focused and diffuse modes respectively.

- Sequential Problem Solving

- Working Step by Step to come up to a solution, works best under focused mode.

- Intuition

- Allowing the diffuse mode to make links across chunks to intuitively grasp a creative solution to a problem.

See the screenshot below for a visual example:

Most new learning and understanding comes about using Intuition, rather than Sequential Problem Solving. This shows why it’s so important to place value in the diffuse mode of learning!

Overlearning & Interleaving

Spinning your wheels learning the same thing over and over again is useless unless you want to develop automaticity (which you might want to do! Good example: times tables).

Overlearning can also increase the illusions of competence effect; so it is recommended that you perform what’s called Deliberate Practice. Deliberate Practice is the intentional focus on the hardest material available. It helps stimulate neuron growth, prevent illusions of competence, and solidify chunks.

One must also be aware of the phenomenon of Einstellung. Einstellung is a neurophysical phenomenon where a neural pathway for a certain task is so strongly connected that the brain finds it hard to create new solutions. It’s not necessarily an optimisation thing either; the brain’s “road most travelled” may be completely suboptimal or even ineffective, but because the pathway is so strong it’s hard to create new links between those neurons.

How can we avoid the Einstellung effect? You can use Interleaving. Interleaving is where the best quality learning happens; you incorporate different already learned chunks into the learning experience when mastering new material. This helps develop multiple alternative approaches to solving problems. An example is different ways of solving simultaneous equations; substitution and elimination methods.

Ultimately, just knowing how to solve problems isn’t enough when you’re looking to apply chunks. The when is also important, as this enables you to build flexibility, creativity and generalisation into your application of learned material. Consider that scientific revolutions are disproportionately brought about by two groups; young people, and people new to the field. This is because they are not mired in einstellung.

Twitter

Google+

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Pinterest

Email